How to Teach Listening Workshop January/February 2019

How to Teach Listening Workshop

People never listen without a purpose, except perhaps in a language class

-Gary Buck

The characteristics of spoken English

- Because listening takes place over time, not space (on paper), the gaps between words that exist in writing do not exist in speech, so the listener imagines them into being. This segmentation of words from the flow of speech (recognizing word boundaries) is often problematic for listeners:

- Jimi Hendrix - “‘scuse me while I kiss this guy” instead of “‘scuse me while I kiss the sky.”

- Elision, assimilation, intrusion and connected speech are potentially problematic for listeners, but not for readers.

- Listening is often interactive, where reading is not. Non-verbal communication is involved. This is why emoticons were invented for writers.

- Pitch, intonation, tone, volume and patterns of stress call all make words come alive. Conversely, great speeches when later read as transcriptions, often come across as mind-numbingly dull because the drama of live interaction is missing.

- The spontaneity involved in most speech means that false starts, hesitation, redundancy, and ungrammatical sentences are extremely common, whereas writing usually involves well-formed sentences and careful advance planning.

- Most educational systems emphasize reading above listening.

Reciprocal vs. non-reciprocal listening:

- Reciprocal listening involves interaction between two or more people (a conversation). This type of listening allows the use of repair strategies: speakers can react to looks of confusion by backtracking and starting again; listeners can ask for clarification, ask the speaker to slow down, etc.

- Nonreciprocal listening describes a situation in which the listener has no opportunity to contribute to a dialogue (like listening to the radio). The listener’s lack of control over the input is a crucial issue. This is why it is regarded as more difficult than reciprocal listening.

- Audio recordings in textbooks are all non-reciprocal, which may not help students learn how to interact.

- Another problem is the role of memory in listening. As we process one word, another word is “incoming.” The mind gets flooded with words. Unless we are well attuned to the rhythm and flow of the language, and the way in which a piece of discourse is likely to continue, this can lead to overload, which is one of the main reasons why students “switch off.” The mind isn’t really concerned with individual words.

- We tend not to remember these with any exactitude, but rather the general meanings that they convey. Many students are faced with badly-conceived tasks that test their memory instead of guiding them towards comprehension.

-

The length of input:

-

Most students can only cope with a limited amount of input.

-

Most teachers see extensive listening as something students can do outside of the classroom.

-

Approaches to listening:

- Until fairly recently, it was assumed that most errors in listening comprehension were caused by students mishearing individual words.

- The student heard “plastic bullet” instead of “postal ballots,” for example.

- Recent research, however, suggests that mishearing individual words is not totally what causes mistakes in listening tasks. What happens is that the students know the topic, hear some familiar vocabulary and make wild guesses about the content.

Input:

- Listening to the teacher is the most frequent and valuable form of input during lessons. No other authentic input is as easy to manipulate.

- Incidental vocabulary learning (vocab picked up incidentally through a listening exercise) is mainly achieved due to personal interest or necessity rather than forcing students to listen to it because the coursebook says so.

- Motivation is vital. Some students may be great at understanding sports commentary and really struggle with a dialogue about the weather forecast. L2 listeners become better listeners when they are motivated.

Hearing English in context:

- If students hear highly proficient speakers presenting a budget or ordering a chicken dinner, it will help them do the same more effectively than any explanation or written language summary we can offer.

Predicting:

- Listening is a process of hypothesizing in real time. As one utterance is made, we hypothesize about its meaning. As the next utterance is made, we may be able to confirm or revise our hypothesis. And so it continues. Sometimes our hypotheses are confirmed or negated even before an utterance is completed, we hear:

- “The packets of..." and prepare ourselves for a noun - the packets of what? The sentence continues: “The packets have been delivered” and we revise our interpretation of the of sound.

- L2 listeners, in general, need to guess more than L1 listeners (L1 listeners can listen to their native language with “half an ear”), and rely more on context in order to compensate for gaps in their knowledge of the language.

- Students can be taught to be strategic about their listening. Teachers can point out the importance of predicting. What type of word (a noun? a verb? etc.) should go in the gap?

- Speech usually consists of more words than are necessary (except for scripted speeches, etc.). Redundancy is commonplace as we repeat ourselves and use um and er.

Authentic texts vs. pedagogic texts:

- Discussion question: What do you think are the differences between these two types of texts?

- Scripted dialogues represent nothing like the messiness of real communication in real situations. Question-and-answer sequences are more like that of a quiz show or courtroom interrogation.

- Real language use is messy, less complete and less ordered than the examples in many scripted dialogues.

Planet Money is one example of a good listening resource for students. The content is interesting. The style is authentic and messy—more a conversation than a report. And transcripts are available for every episode.

Pros and cons of using textbook recordings:

- Pros:

- They often include a variety of accents.

- Cons:

- It can be argued that lessons should be student-centered. In a truly student-centered class, the topics should be suggested by the students and not a third party. Motivation is a big factor - if the student is not interested in the material, they will switch off.

- They rarely deal with controversial or topical issues. Textbooks tend to play it safe and usually don’t include the most up-to-date issues because of the time lapse.

- They can be doctored and sound unnatural. They are not interactive and often don’t reflect real-life conversation.

- There is one speed only. Cannot be manipulated according to the student’s level, etc.

- They are often too long.

- The key point is that teachers need to mediate between the textbook and the class, selecting, omitting and supplementing as appropriate. If the recording lacks the interest factor or sounds too unnatural, then the teacher can always omit it or find ways to make it interesting.

Using the transcripts at the back of the book:

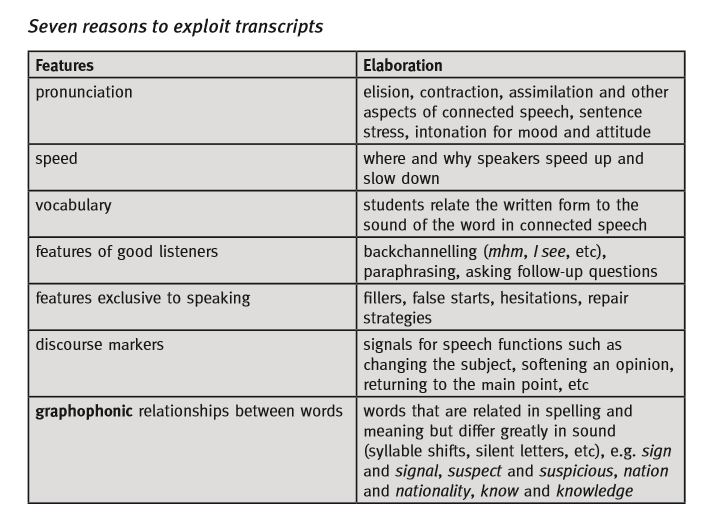

- Many teachers believe that transcripts facilitate cued reading rather than listening.There are compelling reasons for using transcripts. Transcripts allow students to look again, re-read and check. As such, transcripts provide opportunities for students to see the difference between the way words are written and the way they sound. Features such as elision and assimilation are far easier to teach if there is a visible context on paper. Transcripts can be marked up, annotated, kept as reminders of vocab or other features, while recordings cannot.

- Reading from the transcripts allows teachers to control the speed, etc., which allows us to customize to each student’s needs.

- Discussion question: How do you use the audio scripts in class?

- Some ways to use them effectively:

- Teachers can choose to work on only a section of an audio script and use it as a jumping off point to make it more interesting and relevant.

- Questions asked by the learner will always be more interesting to them than questions asked by an outside source. Where possible, encourage students to set their own questions based on the topic.

- Make it more interactive. Ask the student how they would respond if it is a dialogue.

- Ask students to do something realistic with the info they hear. If the students are listening to a description of a place, get them to say whether they would like to go there and why or why not.

- Vary the questions so that there is a balance of intellectual and emotional responses involved.

- Try to incorporate some visual material where appropriate.

- Make sure the answers contribute to the students’ understanding. The idea of comprehension questions is to guide students through a listening passage, not to catch them out.

Listening in the lesson - the sequence:

- Pre-listening:

- Get the student to predict what will happen after reading through the context box in the BR book series. This will prepare the students for what is to come. They will be able to hypothesize more easily and test their hypotheses (adjust it if necessary).

- Ask the student higher-order questions - which ask students to analyze something or personalize the issue, maybe even going beyond the immediate topic.

- Ask students to say how they think the dialogue will go before they listen to it:

- While-listening:

- Current thinking points to one central idea: that students must, in some way, use the info that they hear. The content should demand a response. It should make them think and react. We need to know what our students have understood.

- Students write down key words or exactly what they hear.

- Students are encouraged to interrupt as if they are part of the conversation to clarify and control the dialogue ("Can you say that again please?" "What do you mean by...?" "Would you mind speaking more slowly?" "What does... mean?").

- Listening for gist vs. listening for detail:

- Teachers usually ask students to listen for the overall gist the first time around and then to listen for detail the second time around. If we ask questions that are too specific and try to get the student to pay too much attention to minor details the first time around, they will most likely miss the overall gist.

- Post-listening:

- If the student didn’t understand something, where was the breakdown in communication? Was it due to unknown vocab? The speed? Pronunciation?

- Get the student to summarize what they heard.

- Open up a discussion about the topic.

- Genre-transfer. Ask the student to transfer the material to a more interesting or relevant genre.

- Ask the student to explain what they would have done if they had been a part of the dialogue they listened to.

Source:

How to Teach Listening (Pearson - Longman) by JJ Wilson